A survey of tree establishment, growth and mortality shows that the rate at which Amazonian tropical forests take up carbon dioxide has slowed since the 1990s, whereas signs of a potential slowdown in Africa appeared only in 2010.

The total area of the world that is covered by tropical forest is declining because of deforestation, land degradation and fires — a trend that has increased over the past few years1. At the same time, human-induced climate change is altering the functioning of tropical forests2. During the 1990s and early 2000s, structurally intact tropical forests actively removed carbon from the atmosphere (in the form of carbon dioxide) through photosynthesis, and stored it as biomass. Such forests have been responsible for about 50% of the terrestrial carbon sink3. Hubau et al.4 report in Nature that this globally crucial tropical carbon sink is becoming saturated in both Amazonian and African rainforests, but with different patterns of change.Read the paper: Asynchronous carbon sink saturation in African and Amazonian tropical forests

Forests act as a net carbon sink when the amount of carbon gained through the establishment of new trees and tree growth is larger than the amount lost through tree mortality. In these circumstances, the quantity of carbon stored in the biomass increases over time. The interplay of carbon gains, losses and stocks determines the period of time for which carbon remains in the forest, which is known as the carbon residence time5.

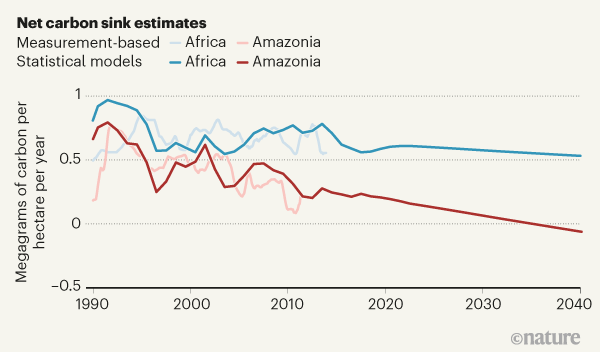

Hubau and colleagues monitored tree establishment, growth and mortality in 244 undisturbed old-growth forest plots in Africa across 11 countries, between 1968 and 2015, and compared their data with similar measurements from 321 plots in Amazonia6. Such long-term monitoring is essential for identifying trends and drivers of the carbon sink in forest biomass, but is highly challenging and costly in terms of coordination, labour and funding — particularly in the tropics, where access to field sites is difficult and working conditions are harsh (Fig. 1). The authors find that the carbon sink in African tropical-forest biomass was stable for the 30 years up to 2015, in contrast to the sink in Amazonian tropical forests, for which the annual net amount of accumulated carbon started to decline around 1990 (Fig. 2). So what drives the slowdown of the tropical carbon sink, and why are there differences between Amazonian and African tropical forests?

The authors report a long-term trend of increasing carbon gains in the forests on both continents throughout the period studied, which correlates with the increase in atmospheric CO2 concentrations. They attribute the rising gains to CO2 fertilization — an increase in carbon uptake by plants that occurs as atmospheric CO2 levels rise. However, they find that increasing mean annual temperatures and drought since 2000 have reduced tree growth and thus offset the increase in carbon gains, with smaller reductions in Africa than in Amazonia.

Hubau et al. go on to show that high carbon gains persisted for longer in Africa than in Amazonia because the warming rate was slower, there were fewer droughts and air temperatures were generally lower (because African forests are located at higher elevations). And, in contrast to an earlier study6, the authors were able to clearly attribute the decline of carbon gains in Amazonia to increasing temperatures and repeated extreme drought events, on the basis of a statistical analysis of their data. The researchers find no signs of the CO2-fertilization effect levelling off on either continent.

Although the authors attribute the decline in carbon gains on both continents to climatic drivers, other limiting factors might be responsible — such as competition between trees for light and nutrients, and the general availability of nutrients on each continent. These factors were not considered in their statistical analysis, but might further constrain tree growth and weaken the sink as atmospheric CO2 concentrations continue to increase. Such limitations have been hinted at from experiments in which the atmospheric concentration of CO2 is enriched in a specific area of an ecosystem7, but no such experiment has been carried out in highly diverse, old-growth tropical forests such as those in Africa and Amazonia.Hyperactive soil microbes might weaken the terrestrial carbon sink

In addition to the trends in carbon gains, Hubau et al. find that carbon losses in Africa were stable from the 1990s until a decade ago, and then started to increase. By comparison, carbon losses in Amazonia had already started to increase in the 1990s. This continental difference seems to be because trees in Amazonia grow faster and have shorter carbon residence times than do those in African forests. Carbon dioxide fertilization might increase growth rate and carbon gains, but it also leads to quicker losses — CO2-fertilized trees grow fast and die young5,6, and therefore might not necessarily contribute to the carbon sink in the long term. The authors find that tree mortality associated with chronic long-term heat and drought leads to increased carbon losses, and that this effect is more pronounced in Amazonian than in African tropical forests as a result of accelerated warming rates in Amazonia since 2000. Data from the most intensively monitored African plots indicate that carbon losses in those forests began increasing from about 2010.

The authors extrapolate their statistical models up to the year 2040, and thereby suggest that the carbon sink will decline on both continents. They estimate that, by 2030, the carbon sink in Africa will be 14% lower than in 2010–15, whereas the Amazonian carbon sink will reach zero by 2035 (that is, there will be no net carbon uptake from the atmosphere). These extrapolations need to be interpreted carefully, however, because they are in striking contrast to projections made by global models — which predict a strong, continuing carbon sink due to CO2 fertilization in intact tropical forests8. Recently reported models9 of vegetation growth that consider nutrient cycling show that the Amazonian-forest carbon sink is strongly constrained by the availability of phosphorus in soils. Hubau and colleagues’ findings underline the need to understand other factors that affect tree mortality and forest dynamics, in addition to such nutrient feedbacks, so that these can be integrated into global models2.

So, what does a pan-tropical decline of the carbon sink in intact forests imply for the current climate crisis? Calculations of the maximum amount of anthropogenic carbon emissions that can be emitted to limit global warming to well below 2 °C — the goal of the 2015 Paris climate agreement — count on the continuation of a large tropical carbon sink10. Hubau and co-workers’ finding that tropical sinks are disappearing and could very soon turn into carbon sources suggests that, as well as strong protection of intact tropical forest, even faster reductions of anthropogenic greenhouse-gas emissions than those set out in the agreement will be needed to prevent catastrophic climate changes.

Source: Nature